The town of Decatur, Georgia, is like a lot of college towns. It’s known for its hip downtown atmosphere, its influx of brainy students, its coffee shops, brew pubs and unique bistros. Decatur sits inside Atlanta’s metropolitan perimeter but is like a whole other world—a safe and sanctified landscape all its own. Decatur is a place children walk to school guided by friendly crossing guards, where a lot of folks still leave their back doors unlocked for the neighbors and where joggers, even lone women, can be seen running all hours of the day and night. You could say it’s a healthy town, American and Southern, which means that racially speaking, it’s a relatively diverse place. Though even in Decatur, tensions can run high around differences. Still, one woman recently made national news when she chose to reach across a seemingly insurmountable gap—race, age, convictions—and calmed a would-be killer, convincing him to turn himself over to police before any real damage was done. Her gentle words and empathic nature somehow stopped this man from massacring children—any of 870 elementary school students at risk of being gunned down by the AK-47-style assault rifle he had brought into their school.

An Astonishing 911 Call

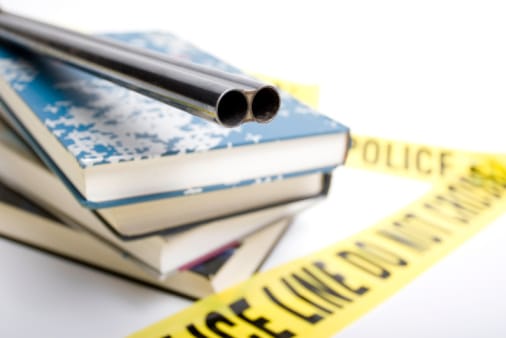

Tuff is a bookkeeper at Ronald E. McNair Learning Academy. On Aug. 20, 2013, Michael Brandon Hill, who is bipolar and schizophrenic, reportedly walked into the school, bypassing the buzzer used by faculty to allow only certain individuals in, with a lethal weapon and 500 rounds of ammunition. Hill had allegedly opened fire on police—firing off at least six shots—and then proceeded to give Tuff instructions to relay to the police with the help of a 911 dispatcher. In the 11-minute recording of the 911 call Tuff placed, she can be heard telling the officers to back up and to cease using their radios except for emergencies. Hill then tells Tuff that he has “nothing to live for” and is “not mentally stable.” Hill admitted having gone off his medication. Initially, Tuff almost sounded as though she were handling a business matter—deliberate and matter-of-fact, relaying the gunman’s wishes to the 911 dispatcher. At around six minutes into the call, Tuff says to Hill, “I can help you. Want me to help you?” She’s encouraging and kind, placing herself at the mercy of the shooter as an intermediary, a kind of ambassador of hope. “Let’s see if we can work it out so that you don’t have to go away with them for a long time,” Tuff says to Hill, speaking to him like a mother or an especially helpful aunt. When Hill indicates that he has made a mistake, that he should have gone to the hospital rather than coming to the school with guns, Tuff encourages him. She goes on to tell Hill, “Don’t feel bad, baby, my husband just left me after 33 years.” Whether she’s aware of it or not, she is doing what experts might do—she is humanizing herself, making herself relatable to the attacker. At Hill’s request, Tuff goes on the school intercom to let everyone know that he is sorry. “We’re not going to hate you, baby,” Tuff assures Hill. An elementary school bookkeeper succeeds in convincing a shooter to give himself up to police and helps him through the process. Later, the 911 dispatcher on the other end of that call would call Tuff her “hero” and say she had missed her calling as a counselor.

Courage of Convictions

How is it that an unassuming Georgia bookkeeper could maintain calm and break through so many barriers in order to reach the man who’d come into her workplace intent on carrying out a massacre and likely his own suicide? Hill is a 20-year-old white male with a prior felony record and a history of mental illness. The suspect’s brother, Tim Hill, told CNN’s Piers Morgan that his brother had been “a normal kid” growing up. But Michael’s behavior changed as he became a teenager, growing erratic and threatening to others. At one point, the teenage Hill had set fire to his family home, with eight people sleeping inside. The fire was discovered in time and no one was harmed. On another occasion, Hill’s mother awoke to find her son standing above her with a butcher knife. After the incident at the school, Tuff told ABC News in Atlanta, “I just explained to him that I loved him. I didn’t know his name, I didn’t know much about him, but I did love him. And it was scary because I knew that at that moment he was ready to take my life along with his, and if I didn’t say the right thing, then we all would be dead.” A religious woman, Tuft believes God placed her in Hill’s path for a reason; when others call her a hero, she credits God instead.

Bipolar Disorder and Violent Crime

Bipolar disorder and its impact on violent behavior have been too seldom studied. While it is known that most people who receive the diagnosis do not go on to commit violent crimes, exactly how many do is unknown. One longitudinal study released in 2010 showed that 8.4 percent of its bipolar subjects committed violent crimes. The study’s authors came to the conclusion that risk assessment for violence should be made a part of the guidelines for the management of bipolar disorder. It would be unwise to ascribe Hill’s alleged intentions to commit a massacre strictly to bipolar disorder or any other mental illness, but to Tuff, we can surely assign deep personal courage, rare character and a willingness to look beyond differences in order to reach the heart of another hurting human.