“ I think one of the things I can do is eliminate some of the shame and the guilt that comes with families and people who are experiencing addiction.”

Following her feature in Elle Magazine, former Mayor of Nashville, Megan Barry sat down with me to start the conversation that we as a society should be having and to fill in the gaps of the conversation the recovery community is trying to have.

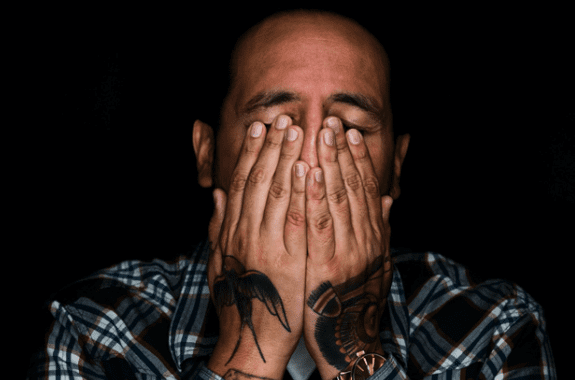

When it comes to addiction and the stigma that is carried with it, it becomes apparent that there is a deeper conversation that we as a society are avoiding. A conversation between family members, friends, loved-ones and even further into our social networks. It’s this lack of communication that keeps addiction in the shadows, rather than shining light on how this disease can be healed.

In her feature in Elle Magazine last month, Megan opens up about the death of her son, Max, to drug overdose. In his death, Megan and her husband made the choice to have the toughest conversation by being honest about Max’s addiction and to share their story with the world. By opening this door, Megan is spreading the message to families to end their shame and speak up about their own stories with children struggling with addiction.

Q: As an advocate for addiction awareness and recovery, what would you say is your current mission and what platforms are you utilizing to make sure your message is heard?

Megan: What I like to think of first is that I am Max’s mom. The stories I tell are grounded in our experience and what Max went through. My hope is that our experience can help someone else. I will go and speak to anybody that invites me to speak. That’s my platform. It ranges from small groups to big groups to companies to media outlets to anybody that picks up the phone and says “Hey, will you come and talk?” And I say, sure.

Q: How can organizations such as Promises Behavioral Health support you in your mission?

Megan: As we start to figure out the different avenues of how to help people, we discover that there are many ways to do so. I think one thing I can do is eliminate some of the shame and the guilt that comes with families and people who are experiencing addiction. And your role as an organization is to make the connection so that they can continue to heal and be healthy for the rest of their lives.

“I think we need to talk about it. I think that’s the one thing that has always been part of the shadows of recovery.”

Q: In your feature with Elle Magazine, you mentioned that the year mark in recovery is the real danger point but that knowledge isn’t widely known, especially to those who don’t understand the struggles of addiction. How can the recovery community effectively get the message across that timely check-ins are necessary?

Megan: I think we need to talk about it. I think that’s the one thing that has always been part of the shadows of recovery. Somehow, we’ve talked about recovery as a moral failure as opposed to an actual biological component. For example, if I knew somebody who had cancer, I wouldn’t be scared to say “Hey, where are you on your cancer journey?”. But we don’t talk to people who are in recovery the same way. We don’t ask “Where are you on your recovery journey?”. We’re not checking in. That one year mark is so critical. We didn’t know and I think it’s pretty typical that if you don’t have a personal experience with addiction that you don’t know. When you are talking about a child (in our experience a 22-year-old boy) who already thinks that they’re invincible that one year mark can be a recipe for disaster.

Q: Being a parent of Max and with all the knowledge you have now, what would you tell your past self or other parents who may be experiencing the same situation with a child struggling to overcome addiction?

Megan: First of all, don’t be afraid to reach and talk about it. I think that for us, we didn’t know anybody else who was going through this at the same time we were going through this with Max, and we didn’t talk about it. I think if we start to talk about this then you can get help to find the resources that you need. I use cancer as an example a lot. If Max had been diagnosed with cancer I would have known five people to call and ask “Hey, where can I get the best help? Where’s the best place to go? What’s the protocol for treatment?” and we would have all been in this together. With Max though, I didn’t know who to call. And I think that speaks more to the fact that we just don’t…talk about it.

Q: Oftentimes, we hear that addiction is a family disease because it affects the entire family. Are there any communities that parents can seek out for support to further help their child?

Megan: There are lots of support groups out there but I think that anyone who is seeking out help should start with their faith community. The faith community has become a lot more proactive in this space and you may find an outlet in your faith community for parents to connect. But I think it’s broader than that. It’s just about having the same kind of frank conversations you have with friends when kids are little. When your kids are little and one of them is doing something behaviorally that you are confused by, you ask other parents. We don’t do the same thing when we’re talking about addiction.

Q: For parents or family members that are grieving their child they have recently lost to drug overdose, what words of comfort do you have for them?

Megan: There’s a lot of stumbling when people try to recognize grief, especially when you have lost a child. I’ve come to appreciate when people are trying to reach out no matter how awkward it may be. I would say that the best thing that you can say to somebody who has lost a child is “I am so sorry for your loss and tell me your child’s name.” Speaking that name out loud is so powerful. And that’s all you need to say. And then if you feel comfortable, you may want a hug. But really those three pieces are all you need to connect.

Q: You mentioned, in the Elle article, how many parents who’ve lost a child due to overdose have hidden the cause of death from being released due to shame and stigma. Given your current platform and visibility on this issue, what would you say to the parent(s) reading now who’ve already made that choice in the past but has had a change of heart but doesn’t know where to start? What advice do you have?

Megan: I recently had some friends tell me about how they lost children to overdose years ago and never spoke about it until now. When you see other families talk about it gives you a little bit more courage. My hope is that if you have lost a child through addiction and you’ve never talked about it to your family or your close friends, that you start with that. Start by saying, “Look, our child passed away because of x.” It’s not going to be an easy conversation. But it’s going to be a conversation that’s going to help others.

Q: The holidays tend to be a hard time for those struggling with addiction. What advice do you have for moms out there with children who need help?

Megan: Gosh, I think a lot of times around the holidays is when you see those children. They may be off at school, or they may live in another part of town or another city and they come back to visit. And that’s when you can potentially see a change in your child. I think having a genuine conversation with your child and putting that shame and guilt away for a minute to acknowledge that there’s something wrong here is always going to be the door opener. Now where that door goes from there is up to the parent and the child. We were lucky because Max was willing to go into rehab but I know that’s not everyone’s experience. That goes back to the shame and the guilt piece. The person who is experiencing addiction has shame and guilt. But just opening that door even a crack might be helpful.

Just by having the tough conversation, families can begin to open the door to recognize there may be a problem and begin the healing process. Organizations such as Promise Behavioral Health can assist in making that connection when the moment calls for treatment but there are proactive steps that parents can take before their child gets to that point.

Dr. Rodney Robertson, Director of Family Programs with The Ranch Tennessee and an expert on how addiction impacts families says “The main reason family members and addicts do not seek help is because of shame. Both parties are concerned about the opinion of others. They believe if the truth comes out people will think negatively about them. To avoid this outcome they try to hide the truth and will often tell lies to other family members and friends in an attempt to escape the dreaded outcome. They would rather ignore the problem instead of bringing the problem to the light. Of course, ignoring the problem simply makes the problem worse and more difficult to manage later when the behavior can no longer be hidden from others.”

Dr. Robertson recommends these proactive steps to help your child before the treatment stage:

- Don’t panic and attempt to take immediate control of the situation

When parents try to control an addict, the control feels smothering and suffocating to that person. This will cause the person to pull away from the relationship. As they withdraw from you, they will turn to the very behavior you are trying to stop because it feels good and the control feels bad. - Don’t shame your child

Shame from a parent has the opposite effect. Shame causes a bad feeling and will drive your child to what makes them feel good to cope with their pain, in this case, with drugs or alcohol. - Don’t enable your child’s behaviors

When the parent does for the child what the child is capable of doing for themselves the parents are enabling the child to continue their behaviors. The parent needs to learn to say ‘no’. If parents keep rescuing the addicted child from the consequences there is no need for the addict to change. - Communicate with and listen to your child

This is the most important and beneficial step that parents can take to better understand what their child is going through. An addicted person never responds well to judgment and criticism. However, when you are willing to listen with empathy and sympathy, your child will open up and begin to explain why they chose the self-damaging behavior as an escape from pain.

By taking proactive steps, you as a parent could potentially save your child’s life and by speaking up about your family experience, you could potentially save the lives of others. Groups such as CoDA and Al-Anon can offer support and resources for parents who aren’t sure who to turn to. Another recommendation is to seek out therapy for yourself. This way, you can focus on your behaviors to further help your child in addressing the underlying issues that come with addiction.

By Chrissy Petrone

Content Writer with Promises Behavioral Health